From Martial Law to Impeachment: Impact on the Economy

The news of the declaration of martial law in Korea on December 3 shocked the world. It is so hard to understand why President Yoon Suk Yeol did it so abruptly, but it is evident that no Koreans would accept it. Thanks to the swift action of the National Assembly, which voted overwhelmingly against it, the law was repealed within about two hours. After the declaration of martial law, Korean citizens gathered in large numbers at the National Assembly, confronting soldiers to prevent its enforcement. The opposition party subsequently filed impeachment charges against the president, accusing him of treason. While the initial attempt failed in a vote on December 7, the impeachment finally succeeded on December 14, with 12 ruling party members voting in favor. On the same day, several hundred thousand people protested near the National Assembly, demonstrating the power of the people to defend democracy.

Picture 1. Protest on December 14, the Day of the Impeachment

Source: namu.wiki

The reasons of the martial law remain mysterious although the president claimed that he felt compelled to act due to what he described as the opposition party’s tyranny, including the impeachment of ministers and significant cuts to the original government budget. Meanwhile, the Korean people are now awaiting the final decision from the Constitutional Court, which is expected within 6 months. The opposition party is pushing for swift ruling, as its leader-the leading presidential candidate- is also on trial. If convicted in the third and final trial, scheduled to take place in five months- he will be barred from the next presidential election.

As political turmoil continues in Korea, people are deeply concerned about the economy, which could be adversely affected by the ongoing instability. The Korean stock market index dropped after the announcement of martial law but partially recovered after the impeachment. However, the Korean currency, the won, has suffered a loss in value, declining from 1405 won per dollar on December 2 to 1451 won on December 23, with no signs of recovery as the following graph shows. The prolonged political uncertainty may undermine credibility of the Korean economy. Standard & Poor’s said that “The declaration and rapid repeal of martial law in South Korea is highly unusual for a sovereign nation with an ‘AA’ credit rating. the overnight events may have undermined perceptions of political stability among investors… normalizing investor sentiment will take more time,” although it noted that there is low likelihood of any change to South Korea’s credit rating within the next one to two years.

Graph 1. The US Dollar to Korean Won Exchange Rate

Source: xe.com

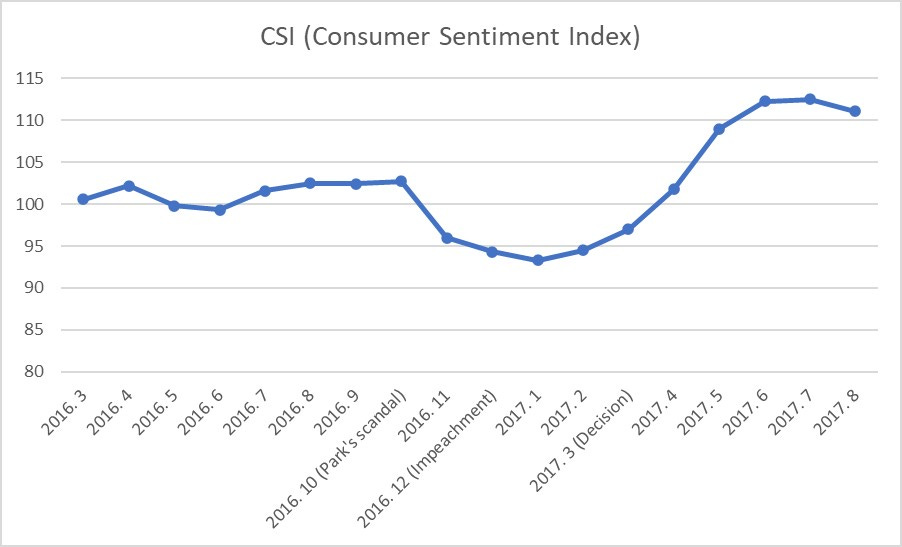

The political crisis is also highly likely to exacerbate the stagnation of domestic consumption until the final decision of the impeachment as it occurred during the impeachment of the President Park eight years ago. Her scandal emerged in October 2016, followed by her impeachment in December 2016. The Constitutional Court issued its final decision in March 2017. As shown in the graph below, the consumer sentiment in Korea sharply declined after her scandal and remained subdued until the final impeachment decision. It subsequently rebounded significantly during the new presidential election in May 2017. The quarterly growth of private consumption in the fourth quarter of 2016 was only 0.2%, much lower than the 0.8% growth of GDP. Based on this precedent, many expect that the impeachment of President Yoon and current political uncertainly will negatively affect domestic consumption and demand for several months until the final decision.

Graph 2. Consumer Sentiment Index during the Previous Impeachment

Source: index.go.kr

The Korean Economy under the Coming Strom

Even before the onset of political turmoil, signs of stagnation in the Korean economy had begun to emerge in the recent period. The annual real GDP growth rate was disappointing, at just 1.4% in 2023. The quarterly real GDP growth rate rebounded to 1.3% in the first quarter of 2024, prompting self-praise from the government. However, it fell to -0.2% in the second quarter and 0.1% in the third quarter, reflecting stagnation of domestic demand and a recent decline in exports. The private consumption shrank by 0.2% in the second quarter compared to the previous quarter due to the depressed real wages, while construction investment and exports fell by 3.6% and 0.2%, respectively, at the third quarter. Notably, net exports contributed a negative 0.8% points to economic growth in the third quarter. In late November, the Bank of Korea (BOK) lowered its 2024 economic growth forecast for Korea to 2.2%, down from 2.5% in August, and projected a growth rate of 1.9% for 2025. International investment banks have presented even gloomier outlooks for 2025, with Goldman Sachs predicting growth of 1.8%. Overall, the Korean economy is facing challenges on two fronts: weak domestic demand, driven by stagnant real wage growth, and difficulties in the external sector. By mid-November this year, the Korea Composite Stock Price Index (KOSPI) and the Korean won’s value against the US dollar had declined by approximately about 9% and 8%, respectively, marking the worst performance among major economies. Small business owners, particularly running restaurants and shops, are bearing the brunt of these economic struggles, with the number of bankruptcies rising in the recent period.

Table 1. Quarterly Economic Growth in Korea (%)

Note: The number in parentheses represents the growth rate, compared to the same period in the previous year

Source: Bank of Korea

Another challenge stems from external shocks. A serious concern has arisen following the election of Trump as the US president. Economic policies under the Trump administration, such as raising tariffs, could seriously harm Korean exports and growth. The stagnation of international trade and the possibility of a trade war are particularly troubling for Korea’s economy, which has recently become heavily reliant on exports. Exports as a share of GDP in Korea kept increasing after the 2000s, driven in part by rapidly growing exports of capital and intermediate goods to China, and has been a major contributor to economic growth. However, Korean exports began to decline in mid-2022 due to shifts in the global economic order, including the retreat of globalization, and the development of domestic industries and an economic downturn in China. While export growth recovered from late 2023, it has once again started to stall in recent months. Additionally, Trump announced plans to reduce government subsidies under the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) for foreign companies investing in the US. This policy change could negatively impact several Korean companies in the battery industry.

Not only are Korea’s short-term economic prospects uncertain, but its long-term outlook also appears rather bleak. One of the biggest challenges facing the Korean economy is the rapid population change. According to the Korean government, the share of the elderly aged 65 and older is already 17.4% of all population in 2022. This figure is projected to rise to 25.3% in 2030, 34.3% in 2040, and 40.1% in 2050, making Korea one of the fastest-aging countries in the world. Moreover, the birth rate in Korea is the lowest in the world, recording only 0.72 in 2023. This is attributed to economic insecurity among young people, difficulty in raising kids, and high real estate prices. The relatively high level of inequality associated with the dual labor market together with the limited role of government redistribution is also associated with the low birth rate. As a result, Korea’s working-age population will decline sharply, leading to slower economic growth in the future. Without a rapid increase in productivity, the country’s potential GDP growth rate is anticipated to fall below 1% by the 2040s.

What the Heck is the Government Doing?

It is natural to ask what the Korean government is doing to manage the economy through its policies. Unfortunately, the current Yoon administration has done little to address the challenges effectively. It has relied on the outdated approach of trickle-down economics, introducing tax cuts for businesses and the wealthy, arguing that economic growth should be led by the private sector. However, there is little evidence to support the claim that such tax cuts stimulate corporate investment and economic growth. On the contrary, they are likely to exacerbate income inequality. In particular, during an economic downturn, tax cuts are ineffective at boosting investment, evident in Korea’s recent experience. Furthermore, the Yoon government has also pursued fiscal austerity, aiming to reduce the fiscal deficit and government debt ratio. This is ironic, given that Korea’s public debt, at about 53% of GDP, is significantly lower than that of many other advanced economies. The administration introduced a highly restrictive budget, with government spending increases limited to 2.8% in 2024 and 3.2% in 2025, lower than nominal growth rates. However, a significant shorth fall in tax revenue has emerge: 56 trillion won (about 2.5% of GDP) below the original budget in 2023, and about 30 trillion won in 2024, because of the economic downturn and tax cuts. This has resulted in a large fiscal deficit, contrary to the government’s stated goals.

Before the Yoon administration, the progressive Moon government (2017-2022) implemented an income-led growth policy aimed at promoting domestic demand and growth by increasing wages and household income. While it was not particularly successful in stimulating economic growth, it aligned with inclusive growth, supported by international organizations and many advanced economies. Though there were certainly limitations in fiscal stimulus under the Moon administration, it still emphasized the role of the state in the economy. In contrast, the conservative, right-wing economic policies of the Yoon administration feel distinctly anachronistic, in 2024, a time when most countries are underscoring a stronger and more active government role in the economy following the pandemic. Under the Yoon government, there has been no consideration of fiscal stimulus or industrial policy involving large public investment at all.

Thus, the approval rate of the Yoon government was already very low – below 20% – even before the declaration of martial law and subsequent impeachment. Many Koreans had been calling for a shift in economic policy as well as an end to the president’s dogmatic ruling style. However, the president declared martial law, leading to the collapse of his government after all. Now is the time for Korea to adopt a new growth strategy centered on a more active role for the government. This should include strong fiscal stimulus and public investment, not only to improve social welfare but also to promote emerging green industries. The economic platform of the opposition party remains still unclear. There are concerns that its stance has become somewhat conservative, particularly in its opposition to raising taxes. Many Koreans are also questioning whether the opposition leader still supports his previously favorable position on basic income. That said, I believe most Koreans would agree both politics and the economy must undergo significant transformation following the current political crisis. Then, the crisis could serve as an opportunity for meaningful changes, enabling Koreans to achieve sustainable and inclusive growth in the future.